NEW YORK, N.Y.— New York State’s system of paying home health attendants who do 24-hour shifts has wage theft built in — and because the money primarily comes from Medicaid, changing that will likely require state action.

“We could do it legislatively or administratively,” says Assemblymember Harvey Epstein (D-Manhattan), sponsor of a bill to end 24-hour shifts.

An unknown number of people in the state receive 24-hour home care, the last line of defense to keep them out of nursing homes. Most of them have one worker there for the full 24-hours, but under state labor regulations dating back to 1960, those workers are paid for only 13 of those hours. Those regulations presume they’ll be off, such as sleeping or eating, during the other 11 hours. That’s a legal fiction, many workers say: They regularly have to do tasks like turning the patient over or helping them go to the toilet.

“It’s an industry based on wage theft,” Jihye Song, an organizer with the Ain’t I A Woman Campaign, a Chinatown-based group working with home-care aides, told LaborPress. “It’s a terrible system for both the patients and the attendants.” And the burden, she says, falls on workers who are almost all women and mostly Asian, Black, and Latina immigrants.

The state’s 1960 minimum-wage order that set the 11-unpaid-hours rule was based on a sexist concept of domestic work, as if they were live-in servants on Downton Abbey, says Assembly Health Committee chair Richard Gottfried (D-Manhattan). “We’re not talking about housekeepers, we’re talking about healthcare workers.”

In 2019, the state Court of Appeals reversed a lower-court ruling that had ordered the state and home-care agencies to pay workers for the full 24 hours. However, it said that they could claim full pay if they could prove they hadn’t gotten time to eat or to sleep for at least five uninterrupted hours. Several smaller agencies agreed to give workers 5½ hours of back pay per shift.

The larger agencies did not settle. But in March, an arbitrator ordered a group of 42 home-care agencies to pay $30 million to cover back wages for 1199SEIU members who did 24-hour shifts and other overtime-pay violations. The union is now processing the data needed to calculate individual payments for an estimated 5,000 to 8,000 workers.

Payments for individual workers will be pro-rated as a share of the $30 million fund according to how many hours they worked and how many 24-hour shifts they did during the six years covered by the settlement, a spokesperson for 1199 told LaborPress. All but one of the 42 agencies involved have provided that data, according to the union. Once that is complete, workers will be sent a notice to file claims. They’ll have 60 days to submit their forms, either online or on paper, and processing will take another 60 days.

Workers will only need to fill in basic information, such as their Social Security number, 1199 says. They won’t have to prove the hours they worked or that they didn’t sleep.

That $30 million sum, arrived at by assessing the agencies $250 for each of the about 120,000 home-care workers 1199 represented during the six years, is significantly short of what would be owed if all the attendants who did 24-hour shifts were paid in full. The most common estimate is that it would cost about $1 billion a year to do that.

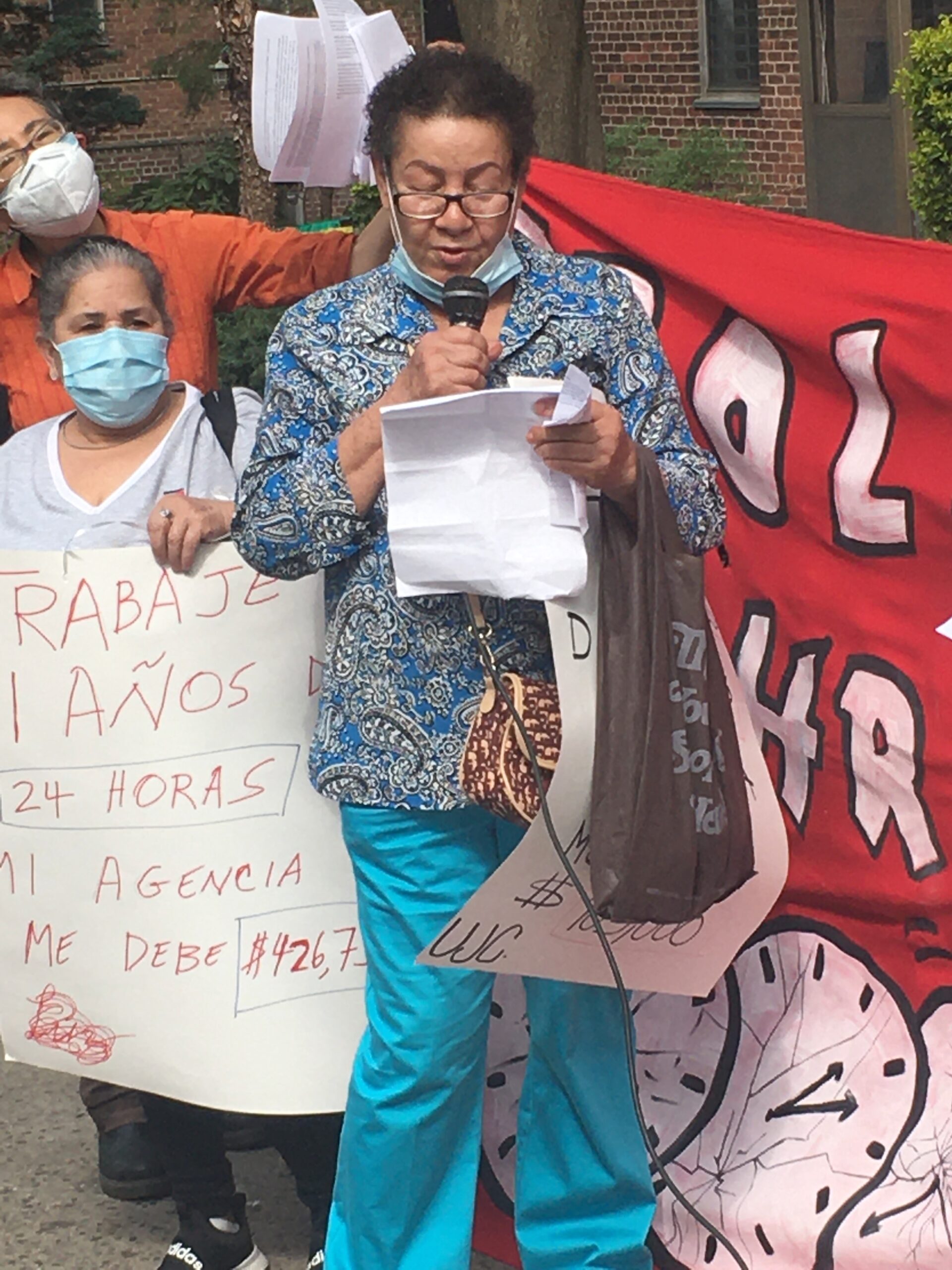

Song estimates that one Chinatown agency, the Chinese-American Planning Council, would owe $90 million for the six years. If a worker did three 24-hour shifts a week, a common arrangement, she would be owed about $25,000 a year.

The arbitrator, however, called the $250-per-worker assessment the “maximum that can be imposed without causing serious disruption and upheaval to a vital service.” If employers had to pay more, he wrote, they might have to close, file for bankruptcy protection, or make massive layoffs.

Several current and former Chinese-American Planning Council workers, backed by Ain’t I A Woman, last month filed a complaint against 1199 with the National Labor Relations Board, accusing the union of failing to represent them on the 24-hour-pay issue, alleging that accepting the arbitrator’s award was acquiescing in wage theft.

“There is no basis for the charges recently filed,” an 1199 spokesperson responded. “The Union has not breached any statutory duties to the workers who filed the charges.” The NLRB has previously dismissed three similar sets of charges filed by this group of workers, the union added.

The union got procedures implemented in late 2015 at the agencies where it represents workers for them to report when they were interrupted during their supposed time off, the spokesperson says.

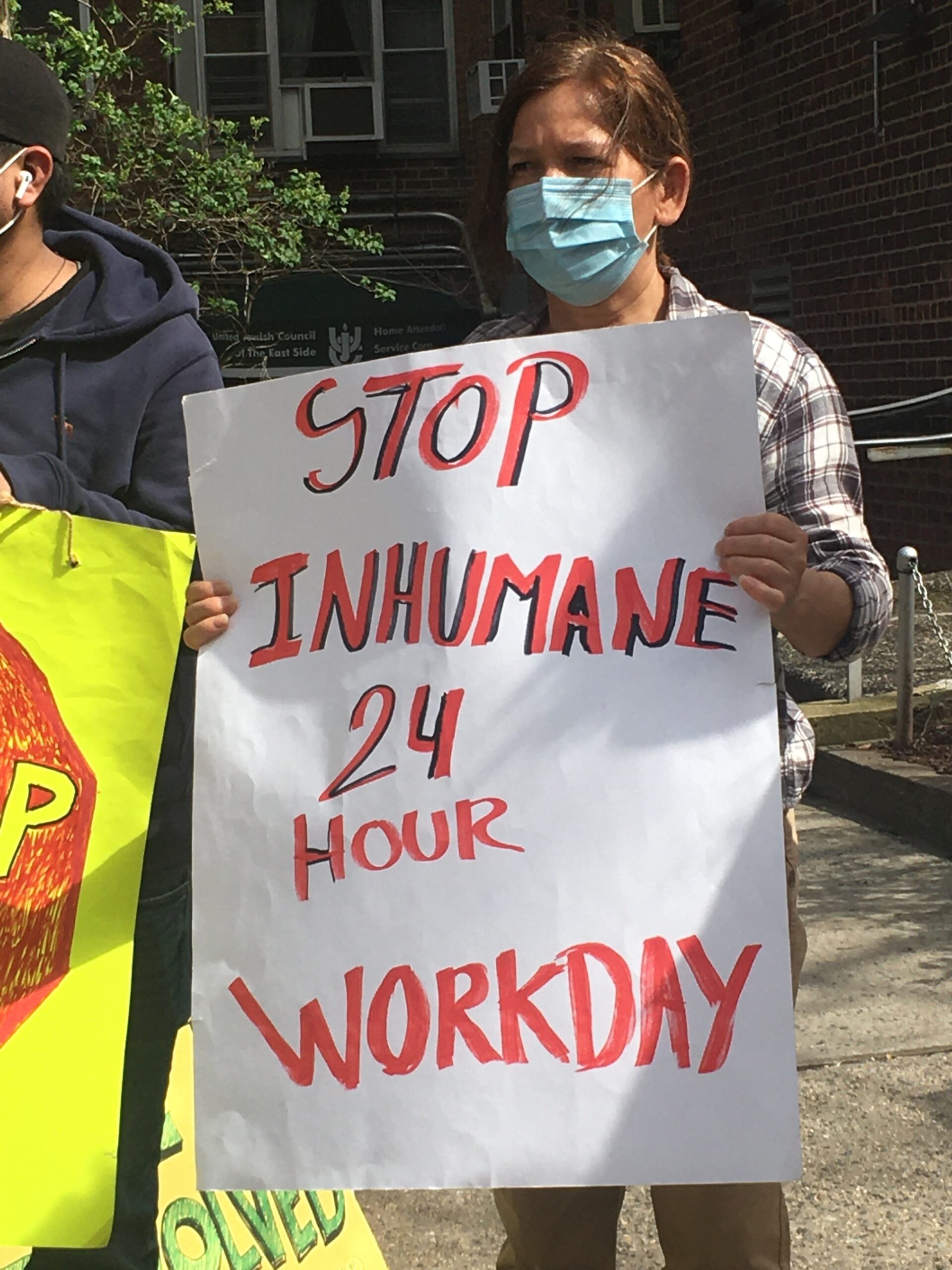

On April 14, home-care workers rallying outside the United Jewish Council on the Lower East Side denounced the agency as a “modern day plantation” and 1199 as a “union overseer.”

“They have robbed workers for years of their wages, their health, their lives — they do this all with the complicity of 1199SEIU who are acting like the custodians of racist violence,” a spokesperson for the National Mobilization Against Sweatshops [NMASS] said.

Home-care workers will next rally at City Hall on Tuesday May 31, ahead of the introduction of a new bill by Councilmember Christopher Marte [D-District 1] seeking to ban 24-hour shifts in the city.

Legislation

Both 1199 and Ain’t I A Woman have supported legislation to end 24-hour shifts, but it has had little success in Albany. Bills introduced in 2019 and 2021 by Assemblymember Epstein and state Senator Roxanne Persaud (D-Brooklyn) did not receive a committee hearing in either house in either session. They would have limited homecare attendants to 12-hours-a-day or 50-hours-a-week, with exceptions for circumstances such as the worker doing the next shift coming in late.

“We didn’t get the traction we needed, but we made progress,” says Epstein. Gov. Kathy Hochul’s main objection, he adds, was the estimated $1 billion price tag. The state and the federal government would be responsible for half each. Medicaid pays 87% of home-care costs, according to the Home Care Association of New York State, a trade group for providers.

Stephanie Luce, a professor of sociology at the City University of New York’s School of Labor and Urban Studies, says spending that money would pay off. Last year, she did a study of the economic impact of the proposed Fair Pay for Home Care Act, a major legislative priority for 1199, which would have raised home-care workers’ pay from minimum wage to $22.50 an hour. That would have cost the state $2.5 billion, but the study projected that it would recoup that from taxes, not having to pay public assistance to workers with poverty-level wages, and the “multiplier effect” on the economy of people spending their additional income.

“Is it a better investment than a sports stadium?” she asks, referring to the $850 million appropriated to build a new stadium for the Buffalo Bills.

The Legislature did not include the act in the 2022-23 state budget. Instead, it gave home-care attendants a $2-an-hour raise effective Oct. 1, with another $1 coming in 2023.

The Labor Department could also end the 13-hour rule, Epstein told LaborPress, which would have similar costs. But he believes the moral obligation is worth the price. If firefighters who sleep on the job in between alarm calls get paid for a full shift, he notes, why shouldn’t home-care workers who take care of seriously infirm people have parity?

“We need to spend this $1 billion, because we’re stealing people’s wages,” he says. “I think it’s a really important economic and social-justice issue. If this industry had a different population, I don’t think we’d see this kind of abuse.”

He plans to introduce the bill again next year.

Additional reporting by Joe Maniscalco