One of the two measures in the Safe Staffing Act package would require hospitals to establish staffing committees, in which at least half the members are nurses or others directly caring for patients, to set “specific guidelines” for the number of patients per nurse on each unit and shift. The other would mandate that beginning Jan. 1., nursing homes must “maintain daily average staffing hours equal to 3.5 hours of care per resident per day by a certified nurse aide, a licensed nurse, or a nurse aide.”

The bills are now on the floor in both houses, and Assemblymember Aileen Gunther (D-Sullivan), their lead sponsor in the lower house, says she expects a vote either Monday, May 3, or Tuesday, May 4. The final versions were introduced Apr. 22 after negotiations involving the New York State Nurses Association, 1199SEIU, Communications Workers of America District 1, and hospital trade groups. In a joint statement issued Apr. 23, 1199SEIU President George Gresham called them “long overdue,” and NYSNA President Judy Sheridan-Gonzalez called them “long-awaited reforms.”

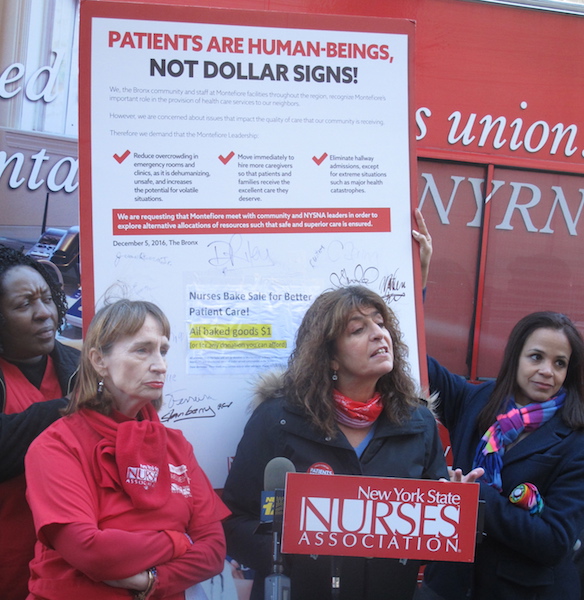

Understaffing has long been one of health-care workers’ biggest complaints. Similar measures have been introduced in every legislative session since 2009, with one passed by the Assembly in 2016, but none ever made it out of committee in the state Senate.

“Nurses have been crying out for this for a long time, and we realized they were right,” says Gunther, a nurse at Catskill Regional Medical Center before she was elected to the Assembly. “It took the pandemic to shake everybody up and say, ‘It’s time. It’s the right thing to do.’”

The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically exposed a problem that’s been festering for a long time, 1199SEIU executive vice-president Milly Silva told LaborPress.

“Staffing was bad before the pandemic,” she says. “It’s been a horror during the pandemic.”

New York generally ranks low in staffing per patient, Silva explains, and the problem is particularly acute in nursing homes. The “gold standard” of care is 4.1 hours per patient, she says, and the 3.5-hour minimum — at least 1.1 hours by a licensed nurse and 2.2 hours by a nurse’s aide or certified nursing assistant — would bring the floor up.

Most nonprofit nursing homes are already close to the 3.5-hour standard, she adds, but “too many” for-profit operators have “bare or minimal staffing, because they’re not required to do more.”

The New York State Health Facilities Association, a trade group representing nearly 400 for-profit skilled nursing providers and adult care/assisted living communities, did not return a phone call from LaborPress.

Nursing-home workers can’t give quality care while “they’re running from room to room,” says Silva. Being able to spend time having conversations with the residents is important to their emotional and mental health — and, during the worst of the pandemic when family members were barred from visiting, staff would sit with dying residents during their last hours, “so they know they’re not alone.”

Feeling that they can’t give adequate care when they’re overloaded is one of the main reasons nursing-home workers think about leaving the job, Silva continues. She recalls three certified nurses’ aides telling her “there weren’t enough of us,” after spending a shift taking care of more than 30 patients, while grieving for coworkers who died.

Adequate staffing, Gunther says, also pays for itself through better patient outcomes, shorter hospital stays and fewer readmissions. Even something as simple as having enough staff to help patients go to the toilet means less incontinence and fewer bedsores.

The legislation, Silva says, would require for-profit nursing-home operators to shift hundreds of millions of dollars into patient care, but she believes that cost could be covered by “dollars that already exist,” through a combination of state aid already appropriated and eliminating schemes such as operators renting buildings or buying bedding from connected companies that charge inflated prices.

“It’s doable,” she says. “It’s necessary.”

“One of the hard-learned lessons of this pandemic is that health-care facilities, such as nursing homes and hospitals, require safe and appropriate levels of staffing in order to provide adequate and reliable care to New Yorkers,” Sen. Gustavo Rivera (D-Bronx), the bills’ Senate sponsor, said in a statement to LaborPress. “My main priority as we engaged in safe staffing discussions with stakeholders was to improve patient safety and enhance quality care across these facilities, as well as to protect our health-care workers. I am proud to sponsor these two bills and strongly believe they will improve the way we serve our elder community, as well as patients in hospitals.”