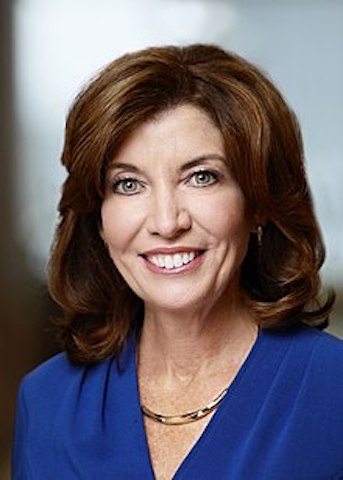

BUFFALO, N.Y.—New York State’s safe-staffing minimums for nursing homes, enacted last year, were supposed to go into effect Jan. 1, but were postponed until Jan. 30 by a last-minute executive order by Gov. Kathy Hochul. Meanwhile, a group of more than 250 nursing homes and trade organizations is suing to stop the state’s mandate, also enacted last year, that caps their profits and requires them to put 70% of their revenues directly into care.

Governor Hochul said she had suspended the rule “in light of the staffing shortage caused by the COVID-19 public health emergency.”

Dennis Short, a senior policy analyst for 1199SEIU, told LaborPress that he understands why the governor didn’t want to create distractions for nursing homes while COVID cases were spiking due to the Omicron variant, but that understaffing was a chronic problem in the industry long before the pandemic hit in 2020.

“It’s one of the things that drive workers away from the bedside,” he says. “It causes so much stress.”

The Safe Staffing Act, signed by then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo last June, requires nursing homes to have enough staff to give each resident 3.5 hours of direct care every day, with at least 1.1 hours from a registered nurse or a licensed practical nurse. Those amounts will be calculated by the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), by comparing payroll data with the daily patient census.

The spending mandate, included in last year’s state budget, requires nursing homes to spend at least 70% of their gross revenues on patient care, with at least 40% going to “resident-facing” staff. If they don’t, they’ll have to pay the difference into a “quality pool” fund intended to increase Medicaid reimbursements for nursing homes. The mandate also limits nursing homes’ profits to 5% a year, with any excess turned over to the same fund.

On average, nursing homes in New York State already meet the 3.5-hour minimum, says Short, “but on the low end, it’s very low.” One big difference, he explains, is that, according to CMS data from the second quarter of 2021, 52% of nonprofit nursing homes in the state had adequate staffing, but only 25% of for-profit ones did.

When there isn’t enough staff, “residents don’t get the care they need and deserve,” says licensed practical nurse Julie Martinez, speaking on her afternoon break at a nursing home in Dunkirk, about 50 miles southwest of Buffalo.

When residents wake up as six in the morning, “you have showers, you have complete bed baths,” which have to be completed before they go to breakfast, she explains. “When you have 30 to 40 people and two aides, it’s impossible.”

LPNs in the morning also have to assemble and pack each patient’s medications for the day. On weekends, when there are only two aides, “we have to hop off the med carts to help them,” Martinez says.

All this adds up to extra hours. “Because we don’t have enough staff,” she says, one day recently she worked from 6 a.m. to 2 p.m., had to come back that night to do the 10-6 overnight shift, and then put in another 12 hours, until 6 p.m. One of her coworkers had to work 33 hours straight.

Some facilities have shown they can hire enough staff to meet the minimum standards, says Short, but that kind of overwork is one reason why retaining staff is difficult.

“The issue is less one of workers being available than of workers staying on the job,” he says. “There has to be enough staff to ensure that someone isn’t just thrown on the floor with 15 or 20 patients.”

“Before the pandemic, we had a lot of vacancies, and now it’s worse. The current staff work double shifts,” 1199 delegate Tonya Blackshear, a certified nursing assistant from Utica, told a state Senate committee last July. “From my experience, for every ten new workers that come into the building, five don’t make it past their probation period and only two make it past the first year…. That means we are seeing over 100 new staff a year, but we can only keep maybe 20. The work is simply too hard for what we are paid.”

Over the last several months, 1199SEIU has won significant pay increases at several nursing homes, says Grace Bogdanove, the union’s vice president for Western New York nursing homes. Their starting wage is $16.50 for CNAs and $24 for LPNs, with higher rates for more experienced workers.

Retaining staff is “about offering competitive wages and benefits,” she says. One of the reasons staffing is so bad at the Dunkirk nursing home where Martinez works is that pay there is much lower; they won’t negotiate a new contract until late next year.

Nursing home lawsuit

The lawsuit challenging the financial penalties for understaffing was filed Dec. 29 by more than 250 nursing homes and three trade groups, including the New York State Health Care Facilities Association. It argues that the limiting their profits to 5% and requiring them to spend 70% of their revenues on care is “an unconstitutional taking of private property for a public purpose,” and is collected “regardless of the quality of care provided.”

It also claims that the fees collected by the state for exceeding the limit on profits or not spending the minimum on staffing violate the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition of excessive fines. It contends that “there is no relationship” between the requirements imposed and the goal of “enhanced quality of care.”

The suit states that if the law had been in effect in 2019, nursing homes would have had to pay $313 million for excess profits and $511 million for not spending enough on staffing. The Brooklyn nursing-home operator KFG Operating Two LLC says that it would have had to pay $7.2 million and $4.8 million. Fairview Nursing Care Center in Forest Hills said it would have had to pay $6.3 million and $5.5 million.

About 73% of the excess-profits fees would come from nursing homes the state ranks in the top 60% for quality of care, the suit estimates, while 79% of the penalties for understaffing would come from facilities in the bottom 40%.

Those figures show that the nursing homes claiming that the law will harm them are both profitable and spending less than the minimum mandated for staffing, 1199’s Short responds. “That’s exactly why we need this law. It’s money that’s earmarked for care.”

Most of those revenues come from Medicare and Medicaid, “publicly funded dollars intended to go to the bedside,” he notes. “They will have to spend that money as intended.”

1199SEIU is also asking the Department of Health to revise its draft regulations, which would determine whether nursing homes were meeting the 3.5-hour care minimum based on the quarterly average reported by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, rather than daily.

That’s important, says Short, because staffing fluctuates during the week, and is often at its lowest on weekends. “That is the pattern in most nursing homes,” he says. “Providers know this happens.”

The Department of Health did not respond to questions emailed by LaborPress. CMS announced Jan. 7 that it would begin publicly posting nursing home staff turnover rates and weekend staffing levels.

Enforcing the staffing minimums daily “would be a tremendous help,” says Martinez. “It would make them up the pay so we could get staffing.”