ALBANY, N.Y.—Gov. Andrew Cuomo on Jan. 1 quietly vetoed a bill that would have allowed workers to put liens on the property of employers they’ve accused of wage theft.

The Securing Wages Earned Against Theft (SWEAT) bill, passed by the state Legislature last June, would have established an “employee’s lien” to parallel the “mechanic’s lien” that a landscaper or construction contractor can put on the property of homeowners who haven’t paid their bills. That would have enabled workers who have filed wage-theft allegations to freeze their employers’ assets while their claims are pending, “to ensure the money is there when the case is over,” state Sen. Jessica Ramos (D-Queens) and Assemblymember Linda B. Rosenthal (D-Manhattan), the bill’s lead sponsors, said in a joint statement Jan. 1. The 10 largest shareholders (or those with the 10 largest ownership interests) of a business would have been personally liable, and the state Department of Labor and Attorney General’s office would have also been able to seek liens.

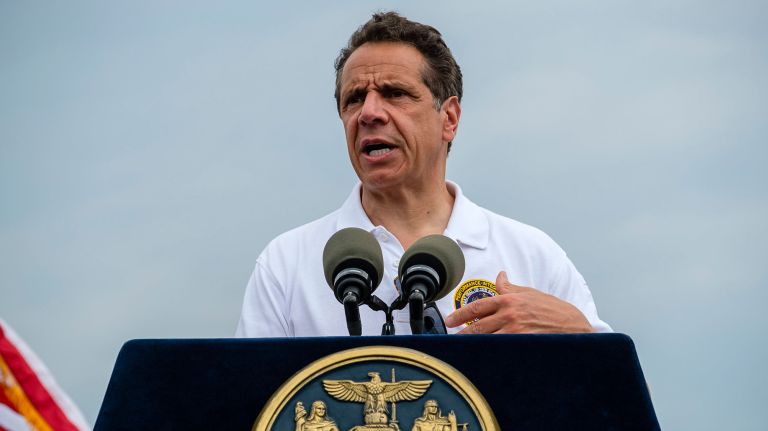

Gov. Cuomo’s veto message said that he supported the legislation’s intent “wholeheartedly,” but he objected that it would allow workers or the state to put a lien on employers’ property before the courts or state agencies had issued a judgment against them. He suggested that would be considered “inadequate due process.” He also said the bill “creates a broad definition of ‘employer’ that includes business entities, owners, and lower-level managers and subordinates.”

“Along with a diverse coalition of more than 100 advocacy organizations and workers, and after years of hard work, we are deeply disappointed by the veto of the SWEAT Bill,” Ramos and Rosenthal said. “This veto hurts the thousands of workers who have been left holding the bag.”

Supporters of the bill argue that putting liens on employers’ property before claims are resolved is essential to ensure that workers who win back pay are actually able to collect it. Ramos and Rosenthal wrote last year that the legislation was necessary because “in too many instances, exploitative employers dissipate their assets or dissolve their business to avoid paying wages they owe to their employees,” and that by the time workers are awarded a judgment, “there are few, if any, assets to be found.”

“The problem is how easy it is for employers to transfer assets under current law,” Flushing Workers Center organizer Sarah Ahn told LaborPress. “If we didn’t have this problem, we wouldn’t have drafted a bill.”

At the Indus Valley restaurant on the Upper West Side, a group of about 10 delivery workers whose employer had paid them less than minimum wage and stolen their tips won $700,000 in 2015. But the owner changed the name of the restaurant to Manhattan Valley, and the workers only collected $110,000. The only reason they got even that, former deliveryman Solomon Perez told LaborPress at a rally outside the governor’s Manhattan offices Nov. 20, was because the “supposed new owner” owed money to the old owner, so the judge had him pay it to the workers instead.

In another case, the owners of a Chinatown restaurant where workers had won a wage-theft judgment transferred their assets and reopened under a new name, former waiter Jinming Vincent Cao told the Nov. 20 rally. The workers got nothing. “They don’t even run away,” Cao added. “We see them walking around Chinatown.”

Cuomo’s veto message echoed the National Federation of Independent Businesses’ arguments. “This legislation puts in place a presumption of guilt on employers as employees would be allowed to put liens on personal or company property on a mere claim of wage and hour violations,” the small-business lobby told its members last June.“The bill also expands the definition of employer to include many parties who have no control over pay practices.”

The NFIB also argued that the bill was unnecessary because there already are state and federal statutes to address wage and hour violations.

Only one other state, Wisconsin, allows wage-theft liens against employers “based solely on allegations, rather than a finding of liability,” the “preventive labor relations” law firm Jackson Lewis wrote in June.

Ahn calls those arguments “fake.” The employees’ lien is modeled on the mechanics’ lien, “which has existed for centuries,” she says. “There is judicial review. It just flips what comes first.”

The bill would have held workers who file fraudulent charges liable for the defendants’ legal costs, she added.

“We really feel that he’s failed working people,” she said of Cuomo. “We crafted this very carefully from the experiences of workers on the ground. We know the obstacles they face.”

The Senate’s 42-20 vote to pass the bill had the two-thirds majority needed to override a veto, but the Assembly’s 87-58 approval was not. Ramos and Rosenthal said they and the SWEAT Coalition are “resolved to continue fighting in 2020.”